The Market, Transportation, and Industrial Revolutions

"It's the economy, stupid." - James Carville

The Industrial Revolution started in Great Britain, using machines to manufacture the natural resources from it’s colonies the world over. Around the same time the Market Revolution was transforming America. It greatly increased after the War of 1812 - known as the Era of Good Feelings - until the outbreak of the Civil War. Essentially, the market and industrial revolutions saw increased production and shrinking transportation times for goods available to the public. No matter what you call it (Market Revolution, Industrial Revolution, etc.), each were long processes and developments inextricably linked to each other, rather than any one specific event; similar to westward expansion, Native American Removal, and European immigration in the 19th century; which all, coincidentally, took place during the same time period.

See also: Satirical take on life in 1800s

In the early years of the American Republic, Alexander Hamilton’s vision of a commercial, free enterprise economy was realized. His plan featured a national bank, market system, and a revolutionary patent system. The free enterprise economic system - or capitalism - dictated that anyone with capital was free to run their own enterprise or business. Technological advances spurred laws of “free incorporation,” allowing corporations to be created without applying for individual charters from the legislature. State legislatures injected capital into the economy by chartering banks. The number of state-chartered banks exploded from only 1 in 1783, to 1,371 in 1860.1 One of the most common features among farmers and business owners in this system was access to credit through the banks. It provided an opportunity to grow their business, but made them susceptible to boom-bust cycles, monopoly power, and distant market forces, as Americans were beholden to prices based on global competition rather than local markets. Boom-bust cycles inevitably created periods of stagnation or recession between periods of growth. Depressions/economic crashes devastated the economy in 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1884, 1890,1893, and the Great Depression in the 1930s. Each lapse in economic growth followed rampant speculation and/or deregulation in various markets. Eventually all the bubbles burst, causing widespread economic hardship. Despite the volatility of a free market, the American economy has more-or-less grown continuously and exponentially since it was established as independent.

At the end of its war for independence, the United States comprised thirteen separate provinces on the coast of North America. Nearly all of 3.9 million people made their living through agriculture while a small merchant class traded tobacco, timber, and foodstuffs for tropical goods, useful manufactures, and luxuries in the Atlantic community. By the time of the Civil War, eight decades later, the United States sprawled across the North American continent. Nearly 32 million people labored not just on farms, but in shops and factories making iron and steel products, boots and shoes, textiles, paper, packaged foodstuffs, firearms, farm machinery, furniture, tools, and all sorts of housewares. Civil War-era Americans borrowed money from banks; bought insurance against fire, theft, shipwreck, commercial losses, and even premature death; traveled on steamboats and in railway carriages; and produced 2 to 3 billion of goods and services, including exports of 400 million. this dramatic transformation is what some historians of the U.S. call the market revolution.

— Professor John Lauritz Larson, The Market Revolution in America (2009)

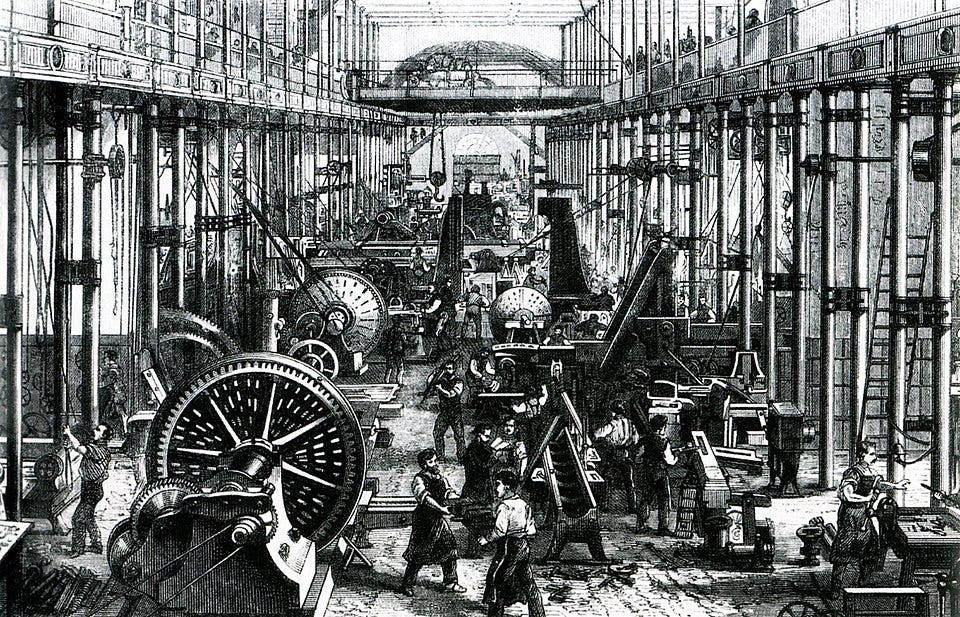

According to economist Douglass C. North, due to the French Revolutionary Wars between 1793 and 1815, the value of American exports rose from $20.2 million in 1790 to $108.3 million by 1807.2 Adversely, in 1816, $9 could move one ton of goods across the Atlantic Ocean or only 30 miles overland.3 The Market Revolution refers to not only how changes in how economic goods were transported but also how they were produced. It changed from artisans and local businesses handcrafting goods in their own homes and communities to industrial mass production in mills and factories (industrialization) owned by wealthy industrialists. The limited power or labor it took to manufacture products before the market and industrial revolutions made them more expensive and scarce.

Transportation and Communication Revolutions

In the late eighteenth century, primitive methods of travel were still in use in America. Waterborne travel was uncertain and often dangerous. Covered-wagon and stagecoach travel over rough trails was slow and expensive. It was not yet economical to ship bulky goods by land across the great distances in America. Turnpike, canals, steamboats, and railways forged a truly continental economy. Transportation innovations cut the cost and increased the speed of moving goods, helping to create a national market and provide a stimulus for regional specialization.

In 1794, a private company completed a broad, paved highway in Pennsylvania, which led the nation in iron production for many years. The highway was called a “turnpike” because as drivers approached the tollgate they were confronted with a barrier of sharp spikes that was turned aside when they paid their toll. In 1811, the federal government began to construct a turnpike—Cumberland Road, also called the “National Road”—which stretched 591 miles from Cumberland, in western Maryland, through Ohio and Indiana, to Vandalia, in Illinois. The project was completed in 1852. In 1829, English traveler Frances Trollope encountered the National Road via Wheeling, VA. It was the first federally funded interstate infrastructure project. She said of her journey across the Alleghenies: “I really can hardly conceive a higher enjoyment than a botanical tour among the Alleghany Mountains.”

In 1807, the first commercially successful steamboat was sent from New York City up the Hudson River to Albany. A steamboat is exactly what it sounds like, a steam-powered boat that could move goods and people along freshwater waterways throughout the country. It was unique for the time as it made waterways 2-way transportation. The invention is generally credited to Robert Fulton. Thereafter, use of the steamboat spread rapidly, with steamers able to reach New Orleans from as far north as Ohio. By 1830, there were more than 200 steamboats on the Mississippi River.

See also: Steamboats on the Colorado and Mississippi Rivers, Steamboats in the West

In 1817, the New York legislature passed a plan to connect the Hudson River with Lake Erie— the Erie Canal. Completed in 1825, the canal ran 363 miles. Its completion moved the country a step closer to connecting the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys, the Great Plains, and the port cities on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. Canals such as the Erie Canal and steamboats revolutionized transportation, and would only be the beginning of industrial travel.

See also: Ohio Canal

Manufacturing and Agricultural Revolutions

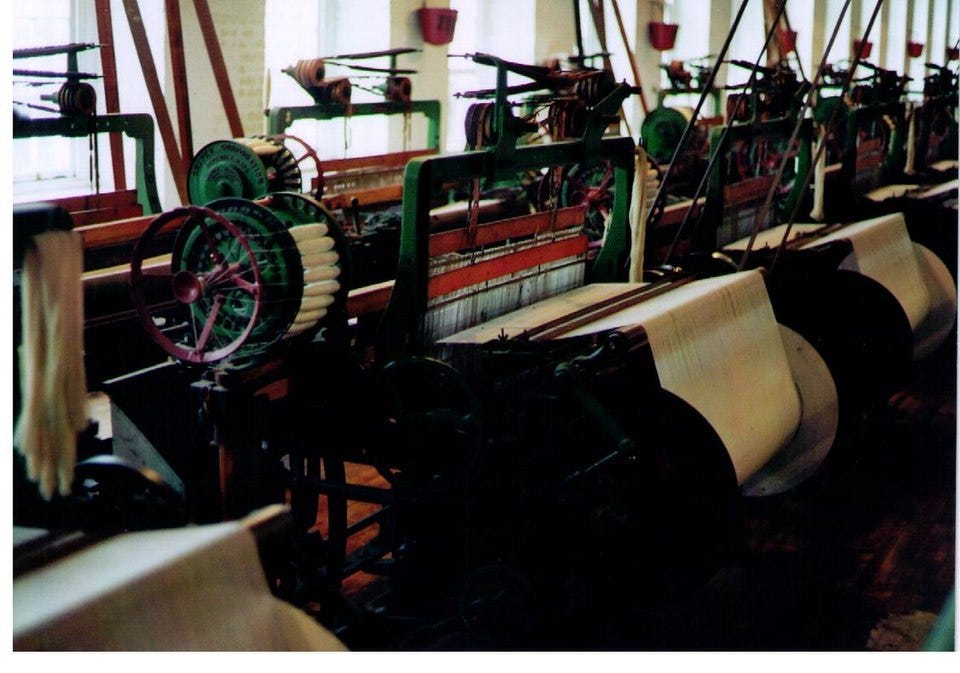

Before industrialization, production consisted mostly of milling. A mill is a machine of ancient design that breaks solid materials into smaller pieces by grinding, crushing, or cutting. There were different kinds of mills, such as a windmill (wind powered) or a watermill (water powered by a water wheel), which milled many products such as sugar, wheat, grains, spices, coffee, etc. Before steam power, most factories and mills were powered by water, wind, horse, or man. Water was a good source of power, but factories had to be located near a river with enough velocity to generate adequate power. Both water and wind power could be unreliable as rivers can dry up during a drought, freeze during the winter, or flood; and wind doesn’t always blow hard enough to turn the sails of a windmill. The technology used in textile mills was invented in Great Britain and was a closely guarded secret. However, in 1789 a textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island contracted Samuel Slater for some corporate espionage. His mission was to steal the designs for a yarn spinning machine (“spinning jenny”) for use in American textile mills. Then, in 1813 Francis Cabot Lowell and Paul Moody were able to recreate the British power loom from memory, a much more mechanized way to weave textiles (cloth, fabric).

Textile mills spun cloth from the cotton plant, grain mills crushed grain into flour, and lumber mills cut trees into nicely shaped boards used for shipbuilding and construction of growing cities and industries. Most American mills were located in New England due to geographic factors like fast flowing rivers running off the nearby Allegheny Mountain Plateau (Northern Appalachian mountains). They were some of the first places to adopt the factory system and railroads to more efficiently manufacture and bring goods to market. The most well-known of these communities was Lowell, Massachusetts; where women and children worked outside the home for wages, rather than production of goods within the home. While it was an opportunity for women to join the labor force outside of the home for the first time, alongside children, they were often overworked and the conditions were dangerous. The employment of women and children helped improve the national economy, but a fight for their rights as laborers and citizens would soon follow. Slave labor certainly had an impact on the market revolution as well. According to Philip Scranton’s book Proprietary Capitalism, “by 1832, textile companies made up 88 out of 106 American corporations valued at over $100,000. These textile mills, worked by child labor and underpaid women, depended on southern cotton, and the vast new market economy spurred the expansion of the plantation South.”4

Which brings us to Eli Whitney and Jevon’s Paradox. In 1793, Whitney devised a mechanism for removing the seeds from the cotton fiber that was 50 times more effective than the hand-picking process: it was called the cotton gin (gin short for “engine”). Whitney hoped to improve the lives of slaves or perhaps even eliminate the need for slaves altogether with his invention. As a result, however, planters in the South expanded the number of acres dedicated to cotton cultivation, thereby increasing the demand for slaves who worked the fields. According to the Minnesota Population Center, “the enslaved population continued to grow, from less than 700,000 in 1790 to more than 1.5 million by 1820.”5 Whitney had unintentionally caused the use of slavery to boom because of the cotton gin. Cotton production soared in the South, between 1849 and 1852 the cotton production in Texas alone, increased from 58,073 bales (500 pounds each) to 431,645 bales. Similar trends were present in Gulf Coast states such as Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana after the Indian Removal Act of the Jacksonian Era cleared the land for (mostly cotton) production. The Civil War saw a decrease in production, but by 1869 it was reported as 350,628 bales of cotton. In 1879 some 2,178,435 acres produced 805,284 bales; and by 1900 more than 3.5 million bales from 7,178,915 acres were produced. The South became known as King Cotton.

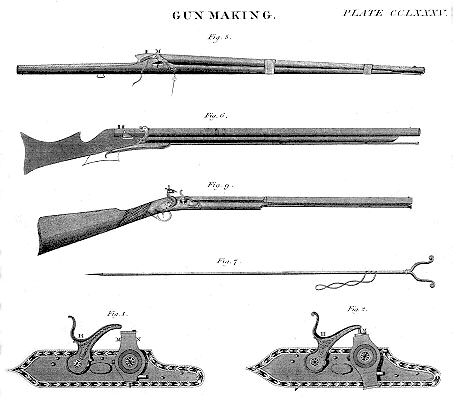

In 1798, Eli Whitney developed another innovation that spurred continued industrial growth in the north. Whitney won a government contract to manufacture muskets. He developed machine tools to make the parts of the musket so they were virtually identical, allowing interchangeable parts. Based on Whitney’s invention, factories for the mass production of firearms were built in the northern states. By the 1850s, Whitney’s method for making muskets led to widespread adoption of the idea of interchangeable parts and eventually became the basis of modern assembly line production methods. It has been said that Eli Whitney both started and ended the Civil War. He started it by inventing the cotton gin, which made raising cotton more profitable and led to an increase in slavery. He ended it by developing a manufacturing process based on interchangeable parts that the North used in its factories, enabling the North to produce far more war goods than the South.

Cotton is a common metric used to measure agricultural production, but subsistence farming saw major expansion as well. Agricultural innovations such as John Deere’s steel-tipped plow and Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reaper allowed more areas to be cultivated by fewer people. Irrigation windmills, or “windpumps,” furthered the closing of the open range, but now allowed cultivation in more places than previously capable by utilizing ground water and aquifers for irrigation. Windmills were also adapted during the Industrial Revolution for irrigation. Irrigation has been a central feature of agriculture for over 5,000 years. It’s the process of bringing water from nearby rivers, lakes, and aquifers to fields for agriculture. The Industrial Revolution saw a much wider application of windmills, or “windpumps” that pumped ground water or aquifer water into fields for crops or livestock. It helps with frost protection, suppressing weed growth in grain fields, preventing soil erosion, cooling livestock, dust suppression, disposal of sewage, and in mining. It was an agricultural revolution in its own right. Agricultural acreage as well as production soared, although similar to the economy as a whole, it would experience over-farming to an extent that a Dust Bowl would devastate the food crop economy during the 1930s. The American Yawp describes the market and industrial revolutions’ impact on the land as “buffalo herds, grasslands, and old-growth forests [giving] way to cattle, corn, and wheat.” The effect of these agricultural innovations was that much more food could be produced by much less people than before, feeding the population boom that America was experiencing at the time.

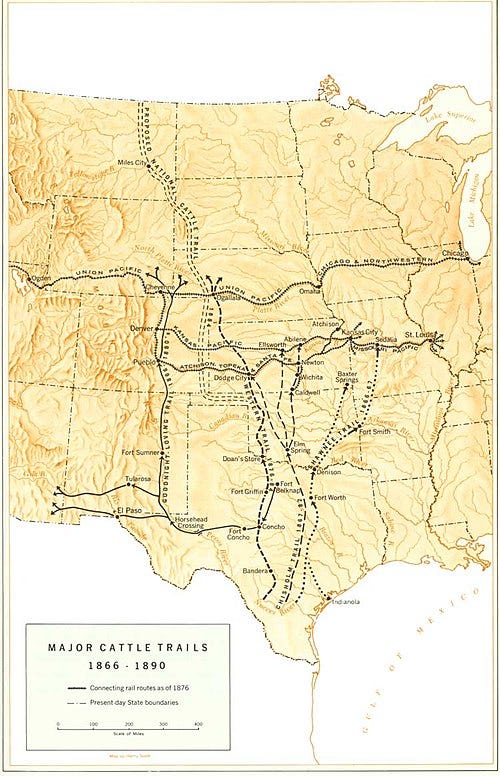

The population grew rapidly for a variety of reasons, but the cattle industry was and still is instrumental in feeding the American population, with strong roots in the Mexican vaquero culture. By the 1800s, a new breed of hardy, disease-resistant Longhorn cattle roamed the southern Great Plains by the millions. Open-range ranching was the difficult job of driving (herding) cattle from ranches on the range/plains to railroad terminals in the western territories to be shipped to urban centers on the east and west coasts. Longhorn beef sold for about $1.50 per head in overstocked Texas, but in the burgeoning cities, the coveted meat went for $30.00 to $40.00 per head. Texas ranchers could make huge profits by moving their herds north on the now-famous cattle trails such as the Chisholm, Western, Goodnight-Loving, and Shawnee Trails. Ranchers and cowboys had to contend with the elements as well as cattle rustlers and hostile Native Americans trying to protect their land from the world's newest imperial nation. Despite the mythology, it has been estimated that up to 60% of all cowboys were Mexican vaqueros or black.6 Cattle trails stretched from Texas and western ranches to Kansas and Missouri stockyards and railroad towns. Famous cattle towns include Fort Worth, Texas, Abilene, Kansas, and Omaha, NE. From the 1860s to the late 1880s, cowboys herded over ten million cattle to market by rail, one million head of cattle per year were shipped to Chicago’s meatpacking centers. Trail drives became obsolete as railroad cars more efficiently moved cattle from Texas to markets on both coasts. The construction of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 connected east to west in a revolutionary way, which exacerbated the trends of industrialization, urbanization, and westward expansion.

By the 1860s, Kansas homesteaders objected to the cattle crossing their land because of Texas Fever, a disease fatal to some types of cattle, yet Longhorns seldom died from the disease. Prices for beef plunged when Texas Longhorns were quarantined as carriers of tick fever. Barbed wire fences put up by private and commercial farming broke up the grazing lands and effectively ended open-range ranching. Barbed wire is a type of steel fence with sharp “barbs” or points invented in 1867 to restrict the movement of cattle, mark property lines, and protect range rights. Large areas became more affordable to fence in as opposed to using Osage orange because barb wire was cheap to manufacture and easy to maintain. One fan of barb wire wrote in 1873, “it takes no room, exhausts no soil, shades no vegetation, is proof against high winds, makes no snowdrifts, and is both durable and cheap.” All of the exploits of the mythological American Cowboy happened in a mere 20 years.

See also: Dust Bowl

What came from the conjunction of the cotton, cattle, and railroad industries was burgeoning cities like Chicago, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Omaha, Denver, St. Louis, Los Angeles among many others. In Chicago, for example, the Union Stock Yards became a hallmark of Industrial America. Historian William Cronon wrote in 2009 that, “because of the Chicago packers, ranchers in Wyoming and feedlot farmers in Iowa regularly found reliable market[s] for their animals, and on average received better prices for the animals they sold there…Americans of all classes found a greater variety of more and better meats on their tables, purchased on average at lower prices than ever before.”7

See also: Charles Hilliard’s Reversing Manifest Destiny

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mr Gibson's Textbook to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.